La poderosa dinastía Habsburgo reinó en España y su imperio desde 1516 hasta 1700, pero cuando ese año el rey Carlos II falleció sin haber obtenido descendencia de sus dos matrimonios, la línea masculina se extinguió y llegó al poder en España la dinastía francesa de Borbón. En la última entrega de PLoS ONE, el profesor Gonzalo Álvarez y sus colegas de la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (España), ofrecen pruebas genéticas que respaldan la evidencia histórica de que la elevada frecuencia de endogamia en la dinastía fue una causa determinante para la extinción de su línea masculina.

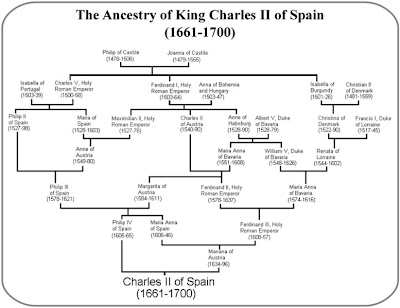

La poderosa dinastía Habsburgo reinó en España y su imperio desde 1516 hasta 1700, pero cuando ese año el rey Carlos II falleció sin haber obtenido descendencia de sus dos matrimonios, la línea masculina se extinguió y llegó al poder en España la dinastía francesa de Borbón. En la última entrega de PLoS ONE, el profesor Gonzalo Álvarez y sus colegas de la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (España), ofrecen pruebas genéticas que respaldan la evidencia histórica de que la elevada frecuencia de endogamia en la dinastía fue una causa determinante para la extinción de su línea masculina.Gracias a la información genealógica del rey Carlos II y de tres mil de sus ancestros y descendientes a lo largo de dieciséis generaciones, los investigadores calcularon el coeficiente de endogamia (F) de cada individuo; este valor indica la probabilidad de que un determinado individuo reciba dos genes idénticos por descendencia debido a la estirpe común de sus padres. Se descubrió que el valor de F aumentaba considerablemente con el paso de las generaciones –de un 0,025 en el caso de Felipe I, fundador de la dinastía, a un 0,254 en el de Carlos II– ya que los monarcas Habsburgo solían casarse frecuentemente con parientes cercanos para preservar la sucesión. Varios miembros de la dinastía presentaban coeficientes de endogamia superiores al 0,20, lo que significa que más del 20% del genoma de esos individuos probablemente fuese homocigótico

Los autores citan tres líneas de evidencias para respaldar la teoría: (1) El gran número de matrimonios entre parientes biológicos (enlaces consanguíneos): (2) el elevado índice de mortalidad infantil y (3) el que Carlos II, conocido como “El hechizado”, sufría distintos desórdenes y enfermedades, algunos de los cuales pudieron ser consecuencia del matrimonio consanguíneo de sus padres.

The powerful Hapsburg dynasty reigned in Spain and its empire from 1516 to 1700, but when that year king Carlos II passed away without to have obtained descendants of his two marriages, the masculine line was extinguished and the power in Spain passed to the French from Bourbon. Gonzalo Alvarez and their colleagues of the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain), offers genetic tests that they endorse the historical evidence of which the high frequency of endogamia in the Hapsburg dynasty was a determining cause for the extinction of its masculine line.

The powerful Hapsburg dynasty reigned in Spain and its empire from 1516 to 1700, but when that year king Carlos II passed away without to have obtained descendants of his two marriages, the masculine line was extinguished and the power in Spain passed to the French from Bourbon. Gonzalo Alvarez and their colleagues of the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain), offers genetic tests that they endorse the historical evidence of which the high frequency of endogamia in the Hapsburg dynasty was a determining cause for the extinction of its masculine line.Thanks to genealogical information of king Carlos II and three thousand of his ancestors and descendants throughout sixteen generations, the investigators calculated the coefficient of endogamia (F) of each individual; this value indicates the probability that individual determining receives two identical genes by descendants due to the common ancestry of its parents. It was discovered that the value of F increased considerably with the passage of the generations - of 0.025 in the case of Felipe I, founding of the dynasty, to 0.254 in the one of Carlos II since the Hapsburg monarchs used to marry frequently with close relatives to preserve the succession. Several members of the dynasty presented/displayed coefficients of endogamia superiors to the 0.20, which means that probably more of 20% of the genome of those individuals was homocygotic.

The authors indicate three lines of evidences to endorse their theory: (1) the great number of marriages between biological relatives (consanguineous connections); (2) the high index of infantile mortality and (3) that Carlos II, known like “The enchanted one”, underwent different disorders and diseases, some of which could be consequence of the consanguineous marriage of his parents.

Tomado de/Taken from Plataforma SINC

Resumen de la publicación/Abstract of the paper

Alvarez G, Ceballos FC, Quinteiro C (2009) The Role of Inbreeding in the Extinction of a European Royal Dynasty. PLoS ONE 4(4): e5174. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005174

Abstract

The kings of the Spanish Habsburg dynasty (1516–1700) frequently married close relatives in such a way that uncle-niece, first cousins and other consanguineous unions were prevalent in that dynasty. In the historical literature, it has been suggested that inbreeding was a major cause responsible for the extinction of the dynasty when the king Charles II, physically and mentally disabled, died in 1700 and no children were born from his two marriages, but this hypothesis has not been examined from a genetic perspective. In this article, this hypothesis is checked by computing the inbreeding coefficient (F) of the Spanish Habsburg kings from an extended pedigree up to 16 generations in depth and involving more than 3,000 individuals. The inbreeding coefficient of the Spanish Habsburg kings increased strongly along generations from 0.025 for king Philip I, the founder of the dynasty, to 0.254 for Charles II and several members of the dynasty had inbreeding coefficients higher than 0.20. In addition to inbreeding due to unions between close relatives, ancestral inbreeding from multiple remote ancestors makes a substantial contribution to the inbreeding coefficient of most kings. A statistically significant inbreeding depression for survival to 10 years is detected in the progenies of the Spanish Habsburg kings. The results indicate that inbreeding at the level of first cousin (F = 0.0625) exerted an adverse effect on survival of 17.8%±12.3. It is speculated that the simultaneous occurrence in Charles II (F = 0.254) of two different genetic disorders: combined pituitary hormone deficiency and distal renal tubular acidosis, determined by recessive alleles at two unlinked loci, could explain most of the complex clinical profile of this king, including his impotence/infertility which in last instance led to the extinction of the dynasty.

Texto completo/Full text